Subjective Objectivity: the Artistic Side to Painleve’s Explorative Films

In his beautifully crafted explorative films, Painlevé captures the intrinsic splendor of our natural world not only through the objective lens of a scientific inquiry, but through his own artistic subjectivity as well. With each spoken word, with each picture, elements of both science and art merge on the screen and the natural worlds come to life in a new, more personal way.

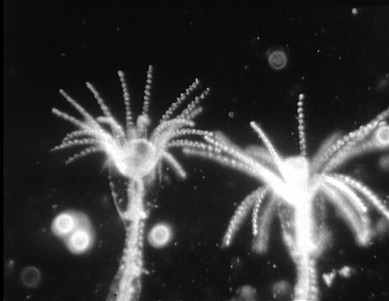

From the early moments of each film, Painleve’s audience is invited to don the scholar’s coat as he or she begins to examine the film’s chosen subjects, whether it be the pulse of a sea urchin or the slinking of an octopus, in their seemingly natural habitat. The films’ narrator, as if a fellow scholar, affably discusses the underwater scenes, drawing the viewers attention to the biology and behavior of the closely scrutinized creatures-the audience is trained early on to come in with a magnifying glass in hand, ready to observe and learn. However, it is not this guided study of the depicted animals and their biology that entrances us in Painleve’s films, but more precisely how he approaches this investigation-not only are we the viewers studying the natural world in Painleve’s works, but the aesthetic world as well through the visual dance of each film. Hidden under every innocent attempt at distant observation or every hardly elaborated quip about some objective quality of Painleve’s creatures is a distinctly subjective aesthetic that transforms the film much beyond the mere documentary.

Taking a closer look at some of Painlevé’s most notable works,L’Hippocampe de Jean (1933) offers an excellent example of the filmmaker’s warm, personal attachment to his films alongside his desire to empirically question their content. The filmmaker’s personal form of curiosity is unmistakable as the viewer witnesses the close-up anguish in the seahorse’s expression as it gives birth or the playful ‘trot’ of these creatures as they race against the horserace projected on the screen at the finale of the film. However, this playful bounce of the sea horses as they frolic in their social exchanges reflects not just an innate charm of these underwater creatures, but more interestingly this exchange between the filmmaker’s desire to learn as well as to create because we then see and hear the narrator’s questions as he carves into the seahorses, turning his tiny companions into slimy pieces of flesh on a cold lab table. It becomes clear that a pursuit of knowledge is heavily present. Yet, even with these seemingly callous points of pure empirical questioning Painleve doesn’t strive in this film only to learn fromthis magical sea world, but to experience his own personal creation as well. From the stark black and white contrast of the seahorses against their ‘theater stage’ to musical symphonies guiding the dance of these water-like sprites, Painleve’s piece almost transforms into solely a piece of art at times rather than any scientific or objective investigation. The film elevates itself beyond the simple documentary namely because Painleve incorporates these beautiful filmic devices that transform his film ‘characters’ into something more than their simple underwater characters.

Simply by coddling his subjects like a caring lover, Painlevé delicately captures these sea creatures in an intimate manner that brings out the human qualities in them all, from the clasp of seahorse lovers’ hands to the assassin-like slinking of the water beetle. With numbing awe, the viewer gets drawn into the beautiful aesthetics of these noble creatures, almost forgetting that this is a real world, a documented moment in life. This approach of personifying the characters supports this hybrid footage rather than forcing a tension between science and art because the craftsmanship of the images pair so perfectly alongside Painleve’s comic commentary. The tension between keeping the study objective and accepting contrasting aesthetic is not relevant- this question is no longer important. Rather, the question essentially shifts towards studying the aesthetic itself instead, and with this pursuit in mind Painleve is allowed the freedom to play both visually and narratively (as a speaking ‘scholar’) in his films.

All in all, Painleve’s talent is self-evident, for if his works were simple documentaries without any overt scientific inquiry or artistic representation, they would still inspire wonder at their ability to capture the unseen. It is ultimately Painleve’s effortless combination of two previously antagonistic realms, art and science, that transformed this works into an even more powerful beauty than they could have realized without. We do not merely observe Painleve’s work distantly like a documentary, analytically like a study, nor admirably as a beauty, but all of this together as the formerly unfamiliar becomes intimate through the lens of Painlevé’s special approach to film and study.

Ashleigh Cote

05.06.2013.